Barking Up the Right Tree: Medicinal Barks of Autumn

By Maria Noël Groves, R.H. (AHG) Registered Clinical Herbalist, Wintergreen Botanicals, LLC

Please Note: The information in this article has not been approved by the FDA and does not in any way intend to diagnose or prescribe. Always consult with your health practitioner before taking any remedy. These plants are generally pretty darn safe – you’ve probably already consumed them in the form of food – but they can still have strong (generally positive, rarely not so positive) actions when consumed in large amounts or on a regular basis.

To be knowledgeable, safe, and connected with your medicine, I recommend that you…

1. Research an herb in at least three good sources before ingesting it (see www.wintergreenbotanicals.com for for recommended reading, articles, and informative links),

2. Listen to your body/intuition to determine if an herb resonates or doesn’t resonate with you.

3. Take proper steps to ensure that any wildcrafted or cultivated plant is what you think it is, AND

4. Check with your pharmacist for herb-drug interactions if you take prescriptions.

Ok, now to the fun stuff!

Barks are an accommodating form of herbal medicine. You can indeed harvest them at any time of year, as long as you know how to identify the plant during all its seasons. Fall is the prime time, though. The sap and energy move freely through the trunks in autumn as the leaves fall away and the trees and shrubs prepare for dormancy. A few lingering leaves aid the budding herbalist in identification, and autumn colors like the vivid yellow black birch leaves act like spotlights as we scan the horizon for our coveted medicines. Working with tree and shrub medicines also invites you to explore the subtleties of botanical identification because the flowers are so rarely present or within reach.

When ~ We typically harvest the bark of a shrub or tree when the leaves are falling off or are absent. Tree bark – especially the inner bark we use medicinally – is the most energetic in spring when the sap is flowing and in fall when the energy of the trees is shifting within the bark from the leaves to the roots. In a pinch, you can harvest small amounts of bark from most plants as needed in summer or winter, but it’s not usually the preferred time.

How ~ The inner bark is the part most often used medicinally. This layer is typically green and sometimes aromatic, between the protective outer bark and structural inner wood. If you harvest large limbs of trees, you’ll need to remove and discard the outer bark. However, I prefer to harvest twigs and younger branches up to one and a half inches in diameter. The outer bark is young enough that I don’t need to worry about separating and removing it. First, prune the twigs and/or branches from a healthy tree or use branches from fresh trees that have recently fallen from natural causes. (Never harvest bark directly from a living tree; this can damage or kill it.) Then use a knife to peel off the bark (both outer and inner); you can use the inner wood for crafts or toss it into the woods to decompose – this isn’t the part we’re using. For smaller twigs, you don’t need to shave the bark at all. Just chop the twigs up.

Here are two of my favorite medicinal barks that are quite common in forests and yards of New England:

Black Birch (Betula lenta) & Yellow Birch (B. alleghaniensis)

Although there are many birches and birch-relatives in the forest, these are the only two trees I know of that pass the “scratch & sniff” test: they both smell like wintergreen, with black (aka sweet) birch being stronger in scent and activity. The bark of yellow birch is shiny and peels on older trees whereas black birch is rough, and younger black birch stems are technically darker, but I have a notoriously difficult time differentiating the two species in their younger years (the bud of yellow birch is hairy, though, whereas black birch isn’t). No matter; they can be used similarly for a nice cup of tea. If I’m seeking to make stronger medicinal remedies, I take care to really key out and get the more potent and delicious black birch. The sap of both trees can be tapped like maple to boil down a wintergreen-y syrup. Use: British herbalist Julie Bruton-Seal extols the virtue of birch sap as a gentle cleansing tonic for spring. The aspirin-like compound methyl salicylate is responsible for the wintergreen scent and flavor of these birches. As such, birch tea and tincture can be used as a mild aspirin substitute for pain and fevers. I enjoy combining it with white pine or hemlock tree needles and peppermint as a brisk winter tea, and I really enjoyed a birch-ginger kombucha made by Darcey Blue French. Birch essential oil may be diluted and applied topically for pain, but take care not to overdo it (see cautions). Bruton-Seal also harvests the late spring/early summer birch leaves for use in tea (spring detoxification, kidney and urinary support, gout, arthritis, and skin issues) and oil (cellulite, detox massage, aches and pains, skin issues). Michael Moore used the fresh leaves in tea for irritated bronchial mucosa in winter (similar to cherry bark) and “lung grunge.” David Winston talks of the Cherokee use of birch in ritual baths to cleanse warriors coming home from war as they adapted back to normal society. The flower essence is used to bring sweetness and graciousness back into your life so that you can give freely of yourself again.

Caution: Use caution with birch if you’re allergic to aspirin; you could also be allergic to methyl salicilate. Both wintergreen and birch essential oils are among the most toxic essential oils due to concentrated methyl salicilate. I enjoy birch bark as an occasional tea with comfort, but if I’m using it regularly in a pain formula, I keep it to 5-15% of the total formula to be safe. If you’re using the essential oil topically, be sure to dilute it well and use sparingly. I wouldn’t use it with children, pregnant women, or anyone with kidney weakness. The leaves are far less concentrated and unlikely to pose these problems. Note: The evergreen Wintergreen Leaves (Gaultheria procumbens) can also be harvested and have similar use as Black Birch, though perhaps a slightly higher risk of toxicity in high amounts or long term use.

RECIPE – Brisk Winter Tea:

This fun, tasty tea is slightly sweet and easy to make with plants growing in your yard.

- 1 six-inch black or yellow birch branch (twigs), fresh or dry, broken up by hand

- 1 handful of fresh white pine needles or 1 teaspoon fresh or dry hemlock tree needles

- 1 teaspoon dry peppermint, optional

- 4 dry whole birch leaves (harvested in spring/early summer), optional

Place the herbs in a 16-ounce thermos with a strainer (or strain later by hand). Cover with near-boiling water and let steep for 30 minutes or longer.

Wild Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) & Chokecherry (P. virginiana)

What wild cherries lack in perfectly plump fruit they make up for in medicinal amaretto-like bark. Wild (aka black) cherry forms the backbone of many a cough syrup and was probably the origin for cherry-flavored cough drops. Chokecherry offers an abundant substitute for the backyard herbalist. They both enjoy disturbed, open ecosystems and can be found along roadsides, yards, and abandoned lots. The bloom early in spring (following the pin-cherry), first the low-growing, egg-leafed chokecherries and then the taller, narrow-leafed (with fuzzy midveins) black cherries, both with clusters of white flowers hanging down like gooseneck blossoms. They are weak trees that attract a variety of diseases and hosts, particularly tent caterpillars and black knot, which can help you identify a stand. In fall you might also be lucky enough to find drooping clusters of fruit on your wild cherries (darker blue/black for black cherries, reddish for chokecherries). These vary in edibility as they are a bit astringent and tart, but they were an important food crop for Native Americans and are a fall favorite for bears. Of course, opt for healthy-looking branches to harvest, which are generally the younger plants. If you’re harvesting in another season, opt to harvest after the plant has flowered. I recommend the “scratch & sniff” test as part of your identification: the scratched cherry bark smells like tobacco and amaretto. Use: Cherry bark is famous for coughs. It helps calm an irritated cough reflex and is best for those annoying, incessant, unproductive coughs. (Opt for horehound in wet, productive coughs.) It nicely quells various respiratory spasms and irritations, lending a hand for folks who live with excess wood smoke and hypersensitive lungs. I like to combine wild cherry bark with another cough remedy: honey. I generally make the tincture of freshly dried cherry bark and then bottle it half and half with honey. Reportedly, cherry bark loses potency once cooked. Freshly made cherry bark tincture (from recently dried bark) tastes divine. (I’m less impressed with that made from store-bought cherry bark, which tends to be less flavorful and more astringent, perhaps because it’s older and coming from aged trees.) It blends well with other lung herbs like mullein leaf, elecampane root, and yerba santa leaf. Although I haven’t used it in its way, cherry bark was used by the Eclectics as a mild cardiovascular sedative for palpitations and the like. Different cherry species yield different flower essences, but a common theme is illumination, clarity, and calm.

Caution: Cherry trees (especially pits and bark) contain small amounts of cyanide-related compounds. These are most problematic in bark/twigs consumed in their wilted state (ie: by livestock) and potentially problematic in extracts made from the pits. It’s a rare but potential risk for people; however, I was taught to harvest bark after the trees flower and to thoroughly dry the bark before further processing it as medicine to eliminate any concerns. Note: Black and chokecherries are the primary medicinal wild cherries. Pin cherries grow around here, too, and are not the primary medicinal species used, though some Native Americans have used it. Pin cherries are obviously different when in flower or fruit – they don’t hang in a long cluster. No flowers or fruits to look at? Check out the leaves (narrow without a hairy midrib underneath) and distal branches (usually covered in spurs/small twigs, with clusters of buds at the ends – which the more medicinal cherries don’t have).

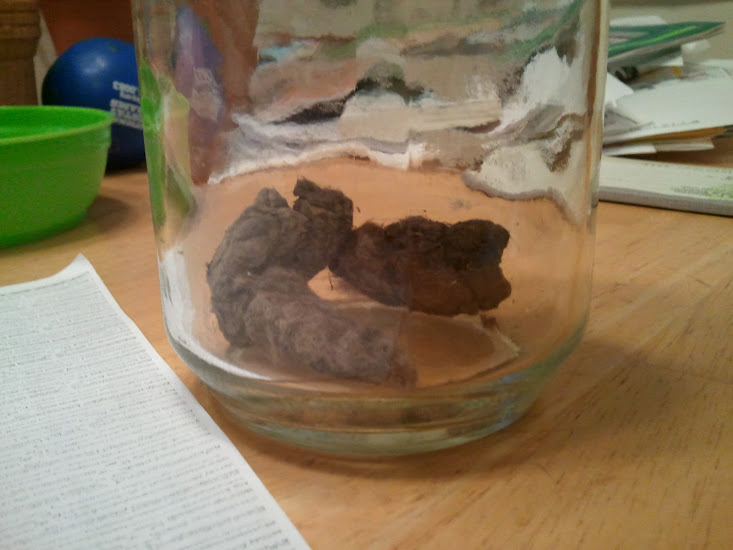

RECIPE – Cherry-Honey Syrup: This gives you the syrup benefit and flavor without cooking the cherry bark and potentially reducing its potency. Loosely fill a jar with freshly dried cherry bark. Cover halfway with alcohol (100- or 80-proof vodka), then fill to the top with honey. Shake regularly and strain after about one month. A typical dose would be 1-4 squirts/dropperfuls (equal to 1-4 ml or up to 1 teaspoon) as needed.

Other Medicinal Wild Barks:

-

Cramp & Viburnum Bark (Viburnum opulus) & Viburnum spp: Smooth muscle relaxer for uterine muscles, cramps. Spring or fall. WILD or CULTIVATED

-

Witch Hazel Bark (Hamammelis virginiana): This astringent bark is most often used topically to tighten and tone tissue, fight infection, and soothe irritation. Common uses include bug bites, acne, cellulite, hemorrhoids, varicose veins, and cuts and scrapes. You can use it as a tea (to make a bath, soak, or compress), topical tincture (just 25-50% alcohol), or try making your own distilled witch hazel extract. Use the infused oil, tincture, and/or shelf-stable distilled witch hazel to make a cream.. WILD

-

White Oak Bark (Quercus alba): Strong astringent for topical use and acute internal conditions. Spring/fall. Other oaks may be substituted. WILD

-

Alder Bark (Alnus spp): Kiva Rose has a lovely monograph on alder on her website. It increases circulation and bloodflow while tightening, toning, and healing tissues. It has application with gut damage, immune infections, toothache, and more. WILD More at www.animacenter.org/alder.html

To learn about drying herbs, making tea, making tinctures, and more, visit:

Click to access HerbalKitchenHandout_1.pdf

Maria runs Wintergreen Botanicals Herbal Clinic & Education Center nestled in the pine forests of Bear Brook State Park in Allenstown, NH. Her first focus is herbal education and empowerment – through health consultations, classes (on-site and online), and writing. She has been working with herbs for nearly two decades and has been trained by some of the country’s top herbalists. She is certified by the Southwest School of Botanical Medicine and was recently accepted as a peer-reviewed professional herbalist by the American Herbalists Guild. Learn more about Maria and access a vast resource of free herbal information at www.WintergreenBotanicals.com.

Lovely nature blog you have here- great posts! :’)

Thank you!